News

DIAMOND GRADING GAMES: THE SEARCH FOR CONSUMER CONFIDENCE

In the wake of the international controversy regarding diamond ‘over-grading' and the subsequent banning of EGL reports, GARRY HOLLOWAY presents solutions that would better serve the industry and build real consumer confidence.

In the wake of the international controversy regarding diamond ‘over-grading' and the subsequent banning of EGL reports, GARRY HOLLOWAY presents solutions that would better serve the industry and build real consumer confidence.

- Diamond industry has slipped into a malaise

- Consumers demand greater transparency

- Instead the industry creates confusion

- Confusion creates mistrust in the consumer

- People won’t buy diamonds if it’s too hard

- Who should lead and drive change?

- Surely not vested interests!

Diamond grading laboratories across the world will be hoping for a quieter year ahead than the 12 months just concluded. What started back in August as a series of lawsuits against the US-based manufacturer Genesis Diamonds had, by year-end, developed into an industry-wide controversy about grading discrepancies and the need for greater uniformity of grading standards. In the centre of it all was EGL International, a prominent grading laboratory banned from having diamonds listed on two online trading platforms (RapNet and Polygon Trading Network) because of over-grading of colour and clarity.

Martin Rapaport, chairman of the Rapaport Group, which owns RapNet, has led the discussion, describing the over-grading of diamonds as an "unfair practice that destroys consumer confidence and the legitimacy of the diamond industry".

After banning EGL grading reports from listing on RapNet, Rapaport effectively endorsed the grading standards of the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) by declaring that RapNet-listed reports must show grades that are within a "reasonable tolerance range" of the GIA standard.

Finding an accepted technological solution – a 'repeatable science' – that can be used by all labs all of the time, as one accepted industry standard, would be the most ideal solution for the consumer; however, the grading trade will be understandably resistant to anything that threatens laboratory business models, strips them of their competitive advantages and large income streams.

Diamond grading labs are paid by diamond manufacturers and dealers to facilitate the sale of their goods. Without labs, the cost of doing business would be much higher and, in turn, result in higher prices for consumers. But make no mistake: the grading labs are not in the business of protecting consumers.

Cry as they might, technology that automates the process is one way forward but it’s hard to imagine that it will happen anytime soon given it would require the co-operation of the GIA, and there would be little incentive for a market leader that generates a net profit of more than $100 million a year to diminish its advantage by sharing grading methods with other laboratories.

REMOVING HUMAN SUBJECTIVITY

Totally automating the diamond grading process with technology is an obvious solution for identifying inconsistent grading standards as it would remove the human factor. It’s surprising that there are not more grading processes performed by equipment and machines given not only the opportunity for greater accuracy but also the obvious cost efficiencies – cutting, for example, involves re-grading at every stage of manufacture, a cost that would drop significantly if it could be automated.

We don’t know for sure how much of the grading process has already been automated by the big labs but we do know there are labs that use colour-grading devices where possible then use a human – or humans – to make the final call on a grade.

Part of the problem from a lab’s perspective is how to make the change from human-based grading to automated grading. The technology may be better and offer more repeatable outcomes than humans but what happens if equipment fails to award the same grade to diamonds that were previously graded by humans? This could result in large lawsuits and greatly impact consumer confidence.

On this topic, it's interesting that labs purport to act as consumer advocates – to protect them – but the cynic in me suggests the labs spend a lot of money and effort identifying previously-graded diamonds just so they can reissue the same grade (rightly or wrongly).

Every diamond dealer knows lab grading is more art and craft than repeatable science. For example, when dealers submit a diamond to a lab they are sent an initial grading report and given the opportunity to challenge it; however, they must pay an additional fee for that privilege.

I am told the dealers often win the challenges and many people feel the challenge process is simply a 'trick' by the labs to raise more revenue from the same client – a diamond graded twice incurs two fees after all. In effect, it means the labs got it wrong the first time, so is there any wonder that consumers can be confused?

All that aside, the way to assess the viability of automation is to firstly consider the grading problems associated with the 4Cs from a diamond shopper’s perspective.

Clarity

In the 1990s, Belgian laboratory HRD attempted to harmonise grading standards across the entire industry. GIA joined the discussions but left at some point. Speculation is that a uniform grading standard would have reduced GIA’s perceived market leadership because every lab would be giving the same grade; however, there were more fundamental clarity standard problems.

From Flawless to VVS1, the difference in grade is a matter of whether an inclusion can be seen with a 10X loupe after being located with a high-powered binocular microscope. This process can be automated based on the size of inclusions measured in microns and the darkness of these inclusions. Black inclusions are graded as worse than lighter whiter ones.

The difference between I2 and I3 low clarity grades is based on the size of the inclusion relative to the size of the diamond. These two grading system rules are in total conflict where they meet in the mid range, around SI/VS.

We know that high clarity determines rarity. You can buy or sell Flawless and VVS diamonds without the need to examine them; grading reports make them fungible. The main factor with lower to medium clarity diamonds is whether you can see the flaws. Eye-clean diamonds are prized, priced on beauty and desirability.

We price diamonds based on a clarity grade set in a lab that is not user-friendly (read: consumer friendly). For example, labs downgrade open cracks, which are politely called 'feathers' on grading reports, because of the risk of breakage. So a SI2 or even an I1 diamond with feathers (cracks) running across the crown facets and the girdle may be totally eye-clean. A VS2 inclusion in a +3ct stone may be easily eye-visible because larger diamonds can have larger inclusions at VS level but a 100ct VVS1 has the same-sized inclusion as a 0.50ct stone.

Does any of this make sense? Definitely not to consumers; they want simplification, not complication. Can a consumer see the inclusion or not? Sadly, many consumers who are chasing the bargain-priced SI/I1 eye-clean diamond get ripped off because the labs are better than we realise at following their own grading rules. For example, almost all +2ct SI2 eye-clean diamonds have some other problem, commonly the risk of breakage or dulling from cloudiness or hazy inclusions.

Since labs do not detail 'sales-killing' notes on their reports, you are never going to see a notation like "this diamond might break" or "this VS2 stone is really dull". OK, I have seen a very dull, small, VS2 GIA-graded diamond and, upon querying GIA lab director Tom Moses, it was confirmed that this was not a mistake.

Fluorescence can, in relatively rare cases also affect transparency but haze or milkiness that results from fluorescence does not, to the best of my knowledge, result in a lower clarity grade.

Colour

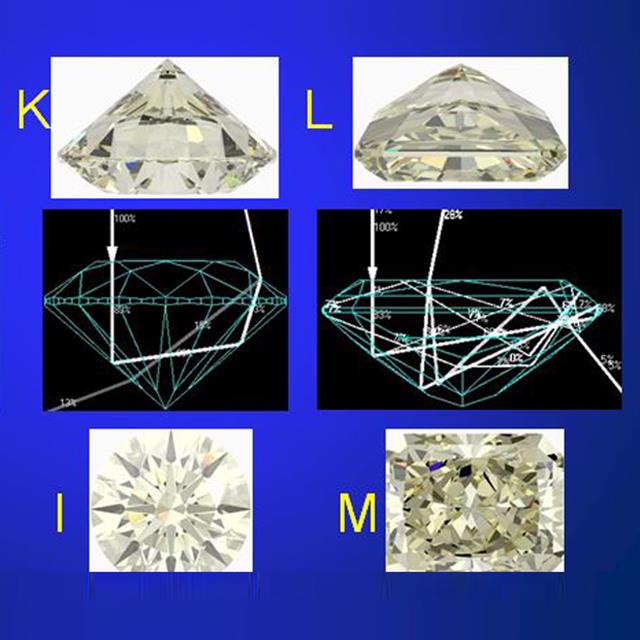

We grade the colour of diamonds face down. Why? Because it’s easier; however, the face up colour of diamonds can be very different, based on the cut shape and cut quality.

Take an H or I-coloured, non-fluorescent +1ct pear or marquise-cut stone and you can easily see the yellowish colour in the pointy tip(s), but the same-sized well-cut round usually needs to be slightly tilted before you can see the body colour. A poorly-cut round typically shows yellow just inside the table region.

If we really wanted to give consumers "objective, unbiased gem evaluations", why do we persist in giving them misleading colour grades?

For example, the several colorimeter grading devices on the market will illuminate and grade the diamond through the pavilion to match the established (flawed) practice. All labs use colorimeters to 'assist' the colour-grading process.

GIA has developed its own device (after initial experimental systems from 1940 onwards) and, in its Gems & Gemology paper on D-Z colour grading in Winter 2008, there is a mention of usage: "In 2001, following its application in the grading of tens of thousands of diamonds, we integrated the device as a 'valid' opinion in the grading process, with visual agreement by one or more graders required to finalise the colour grade of a particular diamond. Since then, the vast majority of diamonds passing through the laboratory have been graded by combining visual observation with instrumental colour measurement. Note that this instrument is for the laboratory’s internal use and is not available commercially."

Historically colorimeters have struggled to accurately grade fluorescent diamonds. Fluorescence does not get its own 'C' but, if present, it often affects the colour of the diamond depending on the light in which a diamond is being viewed. In direct sunlight diamonds will often have a blueish glow, like a white shirt in the black light at a nightclub; some people love the effect, some hate it and many never really notice.

Cut

GIA can only grade the cut of one shape – the round brilliant – and the system they use does not require any visual inspection. For example, a cloudy or hazy, dull round diamond containing cloud or twinning inclusions or fluorescence can receive a GIA 'excellent' cut because the cut rules are based on proportions, polish and symmetry and not on actual appearance. Theoretically, this means a black diamond could receive GIA XXX (Triple X)!

With no gate keeper to grade the cut quality of fancy-shaped diamonds, cutters are free to cheat consumers by saving too much of the rough diamond weight. This means that more than 90 per cent of diamonds, other than round cuts, are poor-quality ugly diamonds.

Fluorescence

I don’t like yellow fluorescence in D to P/Q-coloured diamonds. I do not like any diamond that is hazy or dull because of fluoro; these usually show a petrol-ish over-blue appearance when held right alongside a fluorescent-tube grading lamp.

On the other hand, I like yellow fluoro in yellow diamonds as long as it doesn’t make them hazy, although those electric-yellow, green-fluoro stones that appear hazy in daylight become more attractive. I also like blue fluoro in colourless diamonds and it is very beneficial for pink diamonds because it shifts the colour towards purple and away from brown and orange.

I also don’t like the fact that labs don’t tell you when a diamond will be hazy when UV light is abundant and when the colour in UV-free light drops significantly lower than the reported grade – this was common 20 years ago when GIA used grading lamps that emitted a fair amount of UV.

Michael Cowing, an appraiser in the US, reported a four-grade drop in a diamond from D to H when graded under light that had passed through a Lexan filter, which is a commonly available Perspex. I have some Lexan taped to one end of my favourite grading lamp and it is easy to see how much colour drop there is by shifting the diamonds being graded from the filtered and the unfiltered light.

A one-grade drop is common for GIA-graded Strong Blue fluorescent diamonds when the UV light is filtered out. Is this an issue? Not in my opinion, because normally a diamond is viewed in shaded light by a layperson, which means those diamonds are whiter than their GIA grade would indicate.

SOLUTIONS

The industry’s current problems with over-graded diamonds and the resulting lack of consumer trust need to be addressed. My proposed solutions are based on a common-sense approach from a consumer’s perspective. As we know, common-sense is not common, particularly in industries that have been around long enough to make simple things complex, arguably to the consumers detriment.

Many observers argue that changing anything about grading will result in a lack of confidence because some people will sue their diamond sources claiming they have been misled; however, historically there are precedents – using place names to represent colour (river, etc) or fluorescence causing a high-coloured diamond to appear to be D+ (Premier). In the latter case, there was a substantial drop in value.

Clarity

The industry should forget about trying to create one international standard or 'harmonising' grading systems; we should simply give consumers the ability to see the inclusions in a diamond.

That does not mean using a microscope because that is plain scary and very hard to use. It also kills the emotion of the moment for the consumer. It is far better to use an enlarged photo or even a movie to show exactly where the inclusions are located, and 3D movies are best of all.

We know ‘eye-cleanness’ is the main factor that interests the majority of consumers as most buy lower or medium-clarity diamonds. Everyone in the trade can loupe a diamond, identify where the inclusions are then look with their naked eye and decide if a diamond is eye-clean or not.

Therefore, to increase consumer confidence, let’s call a spade a spade. Labs could describe a totally eye-clean I1 diamond with a crack running around the crown as an SI1 diamond and add the comment, "Eye-clean. Slight risk of breakage; best for earrings or pendant."

We should make it easy for consumers by removing the complications and the jargon. We should make a note about inclusion eye visibility or the milky effect of cloud inclusions on grading reports.

The GIA has several patents on an automated clarity-grading system and there is no reason why such a system could not be adapted to make digital eye-visible estimates.

Colour

Since digital pavilion-based colour grading is already widely available, why don’t the manufacturers develop face-up colorimeters?

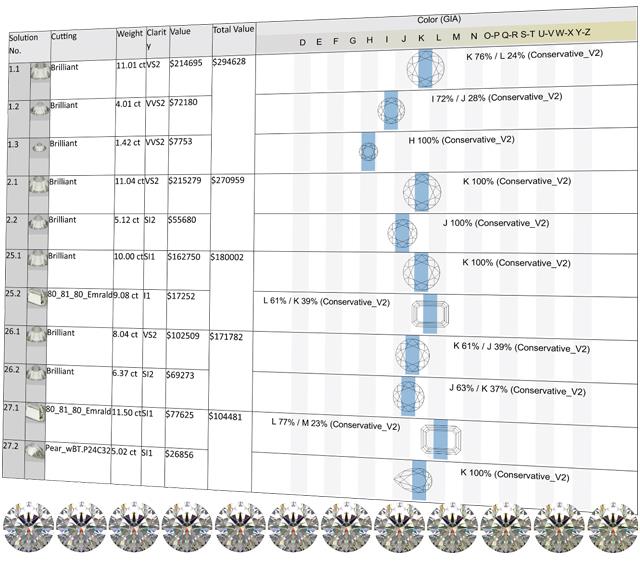

Several diamond-cutting manufacturers are currently using the Oxygen D-Z colour-grading system when planning the cutting of large rough diamonds. This involves measuring the absorption of the rough diamond with a spectrometer and calculating the pavilion and the face-up colour of each prospective diamond with DiamCalc ray-tracing software. Only then is the final decision made as to what stones will be produced from each piece of rough.

Introducing face-up colour but continuing to give pavilion grades would gradually introduce the common-sense approach. Cutting quality and choice of shape would then also improve because better-cut diamonds face up whiter and brighter – consumers will vote with their dollars for the best-looking diamonds.

Cut

Grading cut-quality is the hardest of the four Cs to automate. GIA’s round diamond proportion-based system is not good; the Holloway Cut Adviser, which was patented before GIA’s Facetware, is based on the same method and both indicate a diamond’s potential rather than actual beauty. Neither can be used for fancy shapes.

Many proprietary devices and systems on the market purport to analyse diamond-cut beauty and performance; however, while many have been patented, none have undertaken thorough peer review. The Cut Group, of which I am a member, has recently published significant articles on developing cut-grading systems, highlighting the importance of human stereoscopic vision and other perception complexities that are exceptionally difficult to digitise.

Many leading organisations and experts consider The Cut Group leaders in this area; however, our plans would still take several years to complete, even with appropriate backing. We believe all cuts should be assessed for light performance by comparison to the Tolkowsky ideal-cut round brilliant. Applying the same beauty parameters to both rounds and fancy shapes will set the benchmark higher, which will drive innovation. Cutters and dealers will know that consumers will have proper selection tools.

Proprietary OctoNus digital outputs are closely able to match the human counts of the number, size and duration of fire flashes from actual diamonds in the ViBox that several large Indian diamond manufacturers are using to produce diamond videos for use on their websites or on the B2B listings at RapNet.

Creating effective cut grading tools will lead to the innovative creation of new cuts and improve existing ones. We believe that this is the only real solution to a stagnating industry that will waste money on generic advertising when we need to be reigniting the industry while being more transparent to consumers.

For decades the industry has spent hundreds of millions of dollars telling consumers that "diamonds are forever". Great, but if that’s true, why do consumers need more than one diamond?

In an ever-changing world, we now find that the missing ingredients for the diamond industry are fashion and excitement, are they not?

Carat weight

One of the worst features of our industry is the huge price jump for trigger point or magic weights, for example 1.00ct. This leads cutters to chase yield and push carat weight over those magic numbers like 1.00ct at the expense of the diamond’s beauty.

For example, a more beautiful 0.92ct stone will sell for less than an ugly 1.00ct diamond of exactly the same diameter because people value the trigger point number (1.00ct) more than the beauty. Cut quality suffers. Of course this is just as much the fault of consumers as the manufacturers.

The industry rounds-up carat weight only when the third decimal place is a nine – for example, a 0.998 is a 0.99ct diamond and 0.999 is a 1.00ct stone.

If we used mathematical rounding, 0.995ct would be a 1ct stone. This would give cutters more profits and a little more tolerance to improve the look of the 0.999ct stones to 1.000ct stones.

If you think I am joking, consider this: I searched for 99pt GIA H VS2 on RapNet on January 23, 2015 and found only three stones; however, there was a total 488 stones listed at exactly 1.00ct. Sadly more than half of those 1.00ct diamonds were below 6.3mm diameter, which is smaller than the best cut 0.92ct weight diamond.

Perhaps government watchdogs should intervene; it’s a rip off like buying a 1kg loaf of bread that only weighs 900 grams.

Fluorescence

The large Indian manufacturer Venus Jewel has reported on 'lustre' for many years, giving a human-based grade for milkiness of the diamonds they polish and sell. This is not rocket science; they have master stones and they perform comparisons – the eight-grade scale runs from 'excellent' to 'milky 4'. A diamond’s 'lustre' or transparency can be reduced by fluorescence or by cloudy inclusions.

As mentioned above, it is not difficult to estimate the drop in colour that results from filtering out the presence of UV light when grading colour. This could also be easily digitised in colorimeters. If grading labs were to list any negative effects like milky haziness or colour-grade drops, or even any beneficial rises in colour from CIE daylight standards as a result of fluorescence, then consumers would be fully informed.

In such cases, I would expect blue fluorescence in colourless and near colourless diamonds to result in an increase in the value of those stones; this was the case some 30 to 50 years ago.

SHOW ME THE MONEY!

As a not-for-profit body, the GIA explains its mission: "To ensure the public trust in gems and jewellery by upholding the highest standards of integrity, academics, science, and professionalism through education, research, laboratory services, and instrument development."

GIA's balance sheet for the financial year ending December 31, 2011 recorded a turnover of $216m and showed more than $324m in assets.

That financial data is four years old and, given the GIA’s annual turnover might have greatly increased in the ensuing years due to the enormous increase in demand for graded smaller stones from China, I wonder what the GIA’s latest financial data would show?

This article has set out to discuss some of the ways in which diamond grading can be automated, thus helping the industry to move past a system that currently relies on the subjective view of a human diamond grader.

The EGL over-grading scandal has placed diamond-grading standards at the top of the agenda once more and the industry would be foolish to ignore the controversy this time. There is no reason why consumers should not be given greater transparency while simplifying the sales process to the customer.

So why hasn’t this already been done? Why haven’t labs automated diamond grading? Probably for the same reason that the GIA does not sell its colorimeter technology, which is, as far as I know, the only device it has developed but does not sell to third parties. Why? Well, if anyone can grade any diamond digitally and get consistent and accurate results then who needs labs?

With probably $500 million in assets and annual tax-exempt profits in excess of $100 million, and an outdated, complex process that it designed for verifying a product’s quality, is it any wonder that the GIA has become the world’s largest 'diamond brand'? This is of course ironic given that the business neither manufactures diamonds nor sells them.

Considering all the above, does anyone seriously think that the drive to improve and enhance consumer confidence in the diamond industry will be driven by the labs?

Reference jewellermagazine.